Reflecting on Magic Line

My ascent of Magic Line was not filmed, all there is of the ascent is a string of Instagram posts and some stills taken by Jacopo Larcher, which you can see among the text. In some ways this is nice because I have my actual memory rather than a memory of a film. I wrote a short piece about the route with help from Angus Kille which appeared in a Black Diamond catalogue. This is a less polished longer-form piece which tells the most important parts of the story. If you’re interested in projecting, fear of failure, how to stay present in a process or related ideas you might enjoy this piece!

Jacopo Larcher image

If you ask climbers what they love about climbing, they often talk about how they can use climbing to find their limit and push it further. But I realised at some point in my climbing that this edge, this apparently distinct limit can’t really be an edge or otherwise it would be easier to find. I challenged myself yes, but I always approached challenges knowing I could do them and finished them knowing I could climb harder. Before Magic Line my edge never felt like a real edge, not a knife edge, not even a cliff edge, it was more like a rolling hill, obtuse and undefined. Or maybe I hadn’t been looking hard enough.

I watched other climbers around me collect multiple-year projects. Problem was, none of them seemed happy. You’d always see them dragging their heels on the way to the crag, skin sallow from dieting and an intolerance for conversing about anything other than ‘the proj’. This wasn’t a reason to go climbing in my mind, this was an advertisement to start a new hobby. I was still curious to discover my real limit, yet the deeper question was this: could I keep my head and stay happy in a journey to find the edge of what I was capable of?

It was with this is mind that I ended up half way up the Mist Trail in Yosemite Valley California, late November 2018. In Spring the waterfalls dominate this narrow river-cut valley with dense water vapour and a thunderous roar. In autumn the water fall is but a trickle of its former Spring-self but somewhere along its course it plummets over 96 metres of smooth granite into an emerald plunge pool. This beautiful body of air bubble-whitened water is called ‘Yan-o-pah’ (little cloud) by the humans local to this valley and then, ‘Vernal Falls’ (relating to Spring) by some humans that came later. Both are apt names. As is ‘Magic Line’, a single pitch trad route found just a few hundred meters from Vernal Falls.

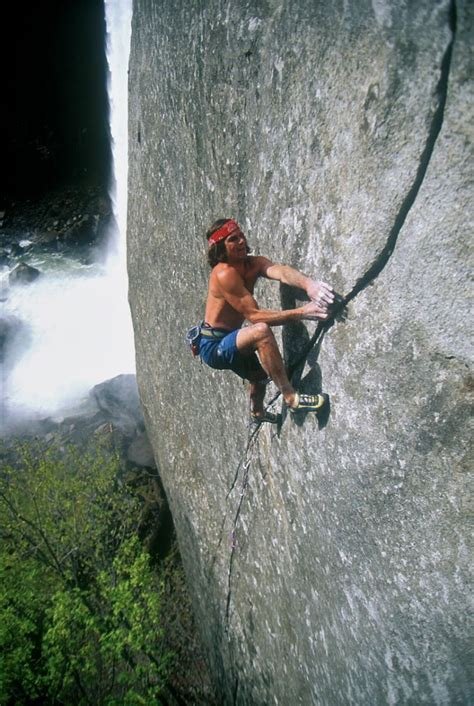

The photos of both Ron Kauk and his son Lonnie (the only two climbers to have climbed this line) are memorable. In both photos they adorn this line with their own charm: Ron with a stylish 70’s bandana and Lonnie with long black braids. Both images oose ‘cool’. But really it isn’t the braids or bandanas that make the photos; it’s the line itself. The graceful sweeping crack cuts through the granite first left then back right like the gentle line a snake leaves in the sand. As many beautiful things are, the line through the rock is delicate and striking all at once. This is no limestone lump, this line has class.

On my first top rope attempt I arrived at the crux and was locked in like the pivotal moves of a chess game, all my attention directed towards a possible solution. I could imagine many possible moves but none of them led me out of check. If I got it right I could haul my body weight off the toprope for a few seconds at a time and as soon as I tried to release a limb I’d be back on the rope. There were poor hand holds, questionable foot holds and a few imaginary sequences. Although I saw no real solution I enjoyed the intrinsic pleasure of trying to bend logic to make the impossible possible. I left the crag confused; maybe this is what a really hard goal is supposed to feel like: the best part of implausible? Later that day the first of the winter storms claimed the valley back from the climbers and I left California with Magic Line now a naive dream, too unrealistic to pay attention to, but not impossible enough to forget.

In the wake of an A2 pulley tear, after 4 months off climbing I was stood on a Mongolian Plateau with my best friend Madeleine Cope. We were about as far away as you could get from Magic Line, both in terms of geography and rock quality.

“What about just training all summer Mads and trying something really cool and hard? Something like Magic Line?” Maddy’s personality is default agreeable but when she said ‘yes’ this time I knew she meant it.

Shortly after our trip to Mongolia I bought a house in Snowdonia National Park in North Wales. It was here in my water-logged homeland, that I began the process of climbing Magic Line, and it wasn’t easy. For the first time in my life I sold my soul to a trainer and a training program. Not one for routine or orders, I swallowed my ego and did everything he said. I’d have to resist the British urge to enjoy the scarce commodity that is the sun, and trust the training plan. Most of the summer I felt too tired to even know if the training was making me stronger, and I was still getting out-bouldered by kids in the gym, but by October I was the strongest I’d ever been.

I committed to a summer of physical training to prep me for Magic Line. But as a mental training coach I was more than aware that I’d need to do some improvements in the brain too. I thought back to other projects and they hadn’t always been pretty. In many cases I had let the pressure get to me. I had become too negative and stuck in the psychology of caring too much about the outcome. I’d knew that the real challenge for me, if I was going to go knocking on the door of ‘my edge’ would be to keep my head, stay happy and accept the challenge for whatever it looked like, each step of the way.

Late October 2019 I met Maddy in Camp 4 and hiked up The Mist Trail. We greeted Vernal Falls and dipped off the tourist trail to the base of Magic Line with all the possibilities on the table and a fizzing anticipation. Dangling on a top rope I returned to the chess game I’d started a year before, but this time I had a mate to help me find solutions. Maddy is built a little different to me, but we are similar climbers with the same strengths and weaknesses. It’s rare for either of us to be able to do more than 10 pull ups. But we can both stand on our feet, open our hips and we have an abundance of climbing tricks up our sleeves.

Magic Line is unique in the way it climbs. It is a crack but it doesn’t climb like one because it’s offset and too thin to jam anything in. Nearly every hand hold faces rightwards so you’re either leaning off the offset edge of the crack or occasionally you can crimp both sides of the crack like you’re trying to prise open an elevator door. Given that all the holds face this way, you can’t use any of the hand holds as foot holds and for that matter all the foot holds are too small to use as hand holds. All those feet-follow problems I did in the gym wouldn’t help me here. Maddy and I spent that first day playing with movements neither of us had done before, marvelling not only at the difficulty but the creativity required to get our bodies to stay on the wall. By evening, mentally and physically exhausted we packed our bags and said ‘bye’ to the Falls knowing that if either of us did this thing we would be stood at the edge of our limit, looking at the space below.

As the weeks progressed so did our ability to link more than one move of the crux in a row. After about 2 weeks we had a sort of sequence. It was completely different to the beta of anyone else we’d seen on the route including Lonnie. It played to our strengths and maximised the use of the best foothold available. In fact we built the whole crux sequence around this one foot hold. We did about 5 hand movements off this one foot hold after which we sprang our foot improbably high to the next good foothold, a move requiring a lot of flexibility. The first time I linked it on top rope I felt like I had sent one project already, and in a way I had: those moves were the hardest moves I’d ever climbed in a row. Soon after, Maddy linked it and there was real cause for celebration: if we could link the crux then in theory we could do the route.

Shoes were a real talking point. We had about 6 different models of La Sportiva shoes. Some were the best shoe for one move but then not a good shoe for other moves. We needed a shoe that was good at edging, jamming and smearing, a shoe that in reality, doesn’t exist. One day I gave the crux a top rope burn to try out Maddy’s new Otakis, the stiffest of the line up and I linked it. It had never felt so possible. I called ‘take’, happy to have completed the moves again and looked down at Maddy to share in the psyche. But she didn’t look happy.

“I heard something come down,” she said. I lowered down and saw a patch of virgin rock where our prise foothold had been and in its place sat a much smaller, rounder and in all ways poorer foothold. Those shoes had been stiff enough to prize it off the wall.

I spent the next hour desperately trying to do the same sequence with the new foothold but I couldn’t do it and neither could Maddy. We left the crag resigned to the fact that Magic Line had moved beyond our edge and into fiction. We went to Curry Village, bought a giant bag of nachos and made jokes about how my fat bum had ruined our chances on Magic Line and what Lonnie would say about us damaging [ruining?] his route.

We often bumped in to Lonnie at the crag. He loves the route so much he was working it for his fourth send (one for every cardinal direction). Yes, Lonnie is a quirky character and it felt apt that he should have been there to observe us through the process of being completely humbled by this route that had, up to this point, stayed in the Kauk family. Much to our relief he wasn’t bothered at all about the foothold, he didn’t really use it anyway and that was the last of the footholds that had been reinforced with glue. The route was now in its cleanest state.

Autumn was tiring, Vernal falls was thinning and the temperatures falling. As the season progressed we collected finger injuries and physical fatigue from the same repetitive movements. We told ourselves we’d find a new solution if we kept hiking up to the line. It was hard to motivate going back up there time again, bodies hurting, minds tired but we were deep in a process and we were committed. Just when we thought we’d exhausted every possible solution, I made a breakthrough and found a tiny side pull next to the crack which allowed us to use a different foothold altogether.

Unfortunately Maddy had to go home. Without my companion the route seemed like a much heavier burden. I realised that I’d needed to do a lot of self-work if I was going to stay happy and motivated without her. My first few lead attempts were a bit of a joke. Passing the first bold meters off the ground and the strenuous reach to place the ball nuts was enough to make the crux a grade harder. But I knew that my body still had some learning to do. There was room for me to become more practiced, precise, focused and efficient. I started visualising the crux every night before bed. I made those moves part of me.

A week before my flight home I went to the crag with my boyfriend. I had no expectations and I had no idea what would happen that day. I tried to see this unknown as an exciting privilege and see how mundane the alternative - of knowing the outcome - would be. I messed up my first few attempts but a flow-like combination of neuro-chemistry got me through the low crux moves on my third attempt. But then the bubble popped and I became a mess of adrenaline and surprise to be where I was. I just about managed to place the cam that would keep me off the ground and willpower alone got me through the middle section of the route and I found myself at the good rest under the final test.

Placing the ball nuts before the crux. Jacopo Larcher image

The final boulder problem of this route is much easier than the lower but it’s just as insecure and tenuous. You really have to climb well over this piece of rock, no amount of finger strength, or power will help you if your centre of gravity is slightly off, or your foot slightly in the wrong place. It’s not enough to have practiced the moves and be strong enough; you need to climb it well and be completely connected to your body’s feedback.

At the rest I spent every second trying to manage my mind and emotions. But my body was adrenalized. I wasn’t really ready to be up there. I did my best, but in one moment of distraction my body wasn’t balanced right, I hesitated and that was enough, I was off. I fell on to the rope in full amazement and excitement: this was my edge, I’d found it.

All of a sudden the end goal was in sight, the achievement was there in front of me, all golden and shining and more distracting than ever before. I knew I didn’t have much time left but I knew it was possible for me to do it this year. I reminded myself that coming back with Maddy in 2020 wouldn’t be a chore but deep down I knew that a lot could happen in a year, that I would be happier to have a different challenge next year and that now was the moment. I was too close. But how can you climb well when you want something too much? The desire to achieve was dragging me in to a future state, but Magic Line required the best of me, which meant being wholly here and now.

With only a few days of my trip left, all my friends had gone and I went up to the crag with a partner I’d met the day before. Third attempt of the day I got through the lower half of the route and I found myself at the rest below the high crux again, and this time I was better prepared. I had been here before. I smoothly and calmly climbed through the lay back moves, feet smearing into the granite with just the right amount of force. I placed the final ball nut as if it was another climbing move, completely locked in to the small bubble of the world that was carrying me up the line. I was about as close as you could get to the jug that marks the end of the hard climbing when I heard a scrunch, a granite crystal under my right foot was causing my foot to slide.

Before the rope had even caught me I could taste in the bitter injustice in my mouth: I deserved this, I had climbed so well and a minute piece of granite had robbed me of my ascent. Why am I so unfortunate? I felt the tears well up and obscure my vision before I saw clearly how foolish I was.

Who is this all important ‘I’ who feels entitled to this route? Life doesn’t work that way, we don’t deserve these things. In reality, I was more than fortunate to be on that route trying my hardest. It’s for those moments that I climb. The tears were my ego. By the time I lowered down to the ground I was OK.

I had two days left. One was a rest day. I spent most of the day alone meditating, writing and holding my head together. I thought of something Lonnie had told me days before: ‘when I want to send this route I won’t even take a call from someone if I think it might bring me bad energy”. Along with him, I was fully aware that I would need a pristine mind for the day ahead.

My friends Babsi and Jacopo had kindly agreed to come up with me to belay and support, the perfect candidates for bringing only the good energy. Under the line we felt the first of the big winter storms approaching and the wind sometimes blew hard enough to sweep some of the waterfall over on to the route, reminding me that there would be no point extending my flight. Tomorrow this route would be under snow, it was today or a year from now and I wanted so badly for it to be today.

The first go I messed up. Second go, feeling a little warmer I climbed well, but as I stretched my foot high to the foothold needed to finish the crux it broke away. I felt defeated. It just wasn’t ‘meant to be’ this year.

I tried again with the remains of the broken foothold and it felt different, harder, and I fell again. I tried to joke with my friends and stay warm, there was talk of giving up but they knew I’d be here until dark if I had to be. Because what did I have to lose?

I tied-in for the final time. It wasn’t pretty but I made it through the crux and found myself at the final rest. I’m not sure I’ve ever spoken to myself as I did at the final rest, on my fourth attempt of the day, last day of the trip, last chance. I tried to speak kindly but seriously. ‘All I can do is be with each move’, ‘I feel grateful to be here’, ‘it’s for these moments that I climb’.

I can’t really say what happened next, there is no marker to the memory other than the moment I became aware that I was holding the final jugs and my feet were in the right spot and my eyes could see the anchor only a few easy moves away. I may have let out some kind of squeal at that point and as I clipped the anchors. I may have said ‘I did it’ to no one in particular. I remember thinking to brush off my tick marks on the way down and I struggled to get the ball nut out and all the time in a state of disbelief, a manic excitement not really knowing which emotion to feel. I hugged and thanked Babsi and Jacopo and we packed up quickly because it was cold.

The following hours and days were strange. I was happy but there was something else nagging at my attention: a colouring of incomprehension and a taste of confusion. How can I suddenly be on the other side of this process? How can it be over? And now that I am holding this shiny gold achievement I’d worked so hard for and wanted so much, I see that there is actually nothing in my hands.

The confusion came from not quite understanding the fact that all the value was in the process. Of course I can tell people I did it, I can claim it as my hardest ascent, I can write an Instagram post about it and my sponsors will be happy. But in reality the ‘achievement' had no value on its own other than to mark the end of the process. Doing the route was just the finish line, the moment it all ended.

The best moments were scattered throughout the process, spent near my edge, climbing creatively, watching the implausible turn to possible, exploring unknowns. The most difficult moments were also amid the process, spent managing my head and emotions, all the time the desire to complete the line was there ready to consume my attention and distract me. This really is the hardest part of completing something near your edge and unlike any other project I’d had, it was my ability to management this process that I’m most proud of. I’ll hold that with me.

Strangely, I don’t even know if Magic Line was my edge or whether edges are like horizons: they get further away as we approach them. All I know is that Magic Line was as close as I’ll ever get to that edge because it was the perfect challenge for me at this moment in my life and for that I’ll be forever in debt to a certain piece of granite next to Yan-o-pah, just off the Mist trail.

Celebration hugs! Jacopo Larcher image